It has probably taken me about ten years to read Robinson Crusoe. There has always been an old copy (it belonged to my great-grandfather) sitting among the books at my grandparents place. On our family’s bi-annual trips to the Eyre Peninsula every summer holidays, I’d pick it up and vow to read the whole thing before we had to leave for the six-hour drive home. I never got very far because I was young and I think the language was beyond me. The next year I was back at it, but still didn’t get past the point I’d begun the year before. There was too much happening with 17 cousins, and aunties and uncles all coming and going. I tried a third time a couple of years later, but eventually gave it up.

Then in June of this year, I had a week staying with Grandpa and Nana and I decided to give Crusoe another go. This was to be my final attempt. I picked it up one evening after a long walk along the cold, wintery shoreline. It worked. Since that summer long ago, I could have read it many times by now, but I am glad I waited. Sometimes a story is just waiting to be read at the right time…

The first edition of Robinson Crusoe appeared in 1719, and is one of the lasting fictional works of Daniel Defoe. Mostly a political essayist, it’s interesting that this single work of fiction is the work for which Defoe is most well-known, and has lasted compared to his other writings.

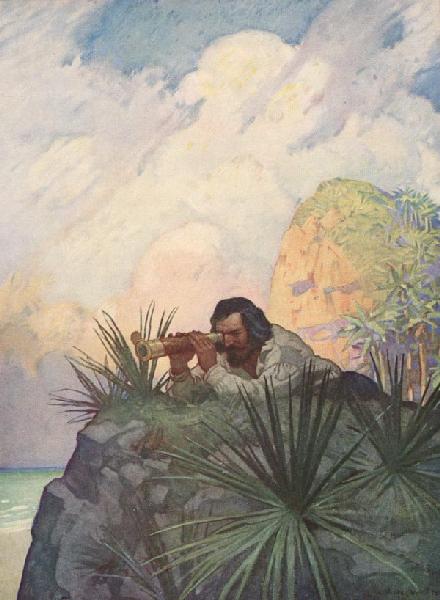

Full of sailors, storms, slavery and (perhaps best of all) the chivalrous, worthy Spaniard, who is very Puss-in-Boots-esque and exotic, Robinson Crusoe is a classic adventure similar to Robert Louis Stevenson’s work, only with more of a historical bent. Told in the first person, it’s a bit like reading a personal travel journal, intertwined with some brilliant storytelling, humour, and wit. I found the story to be a wealth of knowledge and experience: one learnt a host of random, ordinary things about how people travelled ‘back then’: back when the fastest most common source of overland transport was the humble horse, and the quickest way to get to another country that was not part of your own continent was indeed ‘over seas’. I learnt a great deal about sailing and why it would have been so fantastic a profession and yet so terrifying at the same time. Simply fascinating. But to get back at it…

The story is rough and ragged enough in its own way, a real stunning ‘Adventure on the High Seas’ kind of read, told in a tone that is quite matter-of-fact. There are pirates, sailors, wolves and the occassional violent, dangerous character. By the time the story is done, Crusoe has travelled the world quite extensively and the reader gets a real sense of what it was like for an English shipping merchant to do business during the 17th and 18th centuries. The world was not a kind place. One had to ensure they were not sold into slavery or mistaken for a pirate. This happened to Crusoe when he innocently bought a stolen ship and ended up being chased by the Dutch. He got away by escaping to China and had to return home via a long overland journey to France, eventually crossing the channel to England.

There are themes of repentance, redemption and deliverance. There is not much double-crossing. People are actually noble – I kept waiting for some person whom Robinson depended on to turn their back on him but they never did. Promises were always carried through; the people whom he met when in trouble were helpful, selfless to an astonishing degree, and plain decent. This aspect of Crusoe’s interactions surprised me and left me with a lovely pleasant feeling – we are so used to characters in today’s art and literature being base and dishonest, that we forget what true nobility and honour look like. Contemporary books and movies always seem to include some ‘drama’, where a character’s fall is often the part most enjoyed and glorified. For Crusoe, the greatest challenge, indeed the most difficult person he had to face, was himself: his own foolishness, his tendency to be headstrong, his rebellion against God – these were his worst enemies. But after fifteen years surviving alone on an island in the Brazils, suffering had tamed him enough to drive much ignobility from his heart. Though there were times afterward when he’d fall into foolery, he was straighforward about it and told his reader so.

Crusoe gave me an appreciation for the ordinary drudge that is existance, teaching me to just get on with it, and to make the best of things. Because, really, most of life is mundane and repetitive, like climbing a mountain where every rewarding view is covered by fog and the way is steep. He brought me into a world where the ordinary hero faces extraorindary things (it’s vice versa in most modern books) and did it well, teaching him much about life, faith, others, and about himself. And it’s in this lovely place of learning that we both grew together. After 300 years Robinson Crusoe still speaks to the human spirit. And that is the best case for the old books I can think of.

Leave a comment